by Amanda Bullis

TL;DR: The impact of your belief in yourself and care for others might be greater than you think.

I like to be in incubator environments where an idea, project, manuscript, or artwork is in the making. I have been drawn to these environments over and over again in my life in different forms in different industries. My favorite part of acting was the rehearsal process leading up to performance, my favorite part of writing is the the moment an idea pops into my head and the story begins to evolve, taking on a life of its own. I love artists’ studios, science labs, start-ups, design sprints, and writer’s retreats. There is something intoxicating about the energy of a thing in the process of being made. It feels like bearing witness to the birth of life itself. What I have learned about being in these environments over the years is that space, time, and support are necessary for any idea, person, project, or business to grow. A prime example of this need for support, nurturance, and the grace of a second, third, or fourth chance is the story of the father of modern genetics, Gregor Mendel.

I had first fallen in love with this Augustinian monk and the humble pea plant experiments that would become the foundation of modern genetics during an undergrad Biology 101 class. A couple of weeks ago, I traveled to the city of Brno in the Czech Republic for a cousin’s wedding. While doing research on the sights and sounds of the city, I was delighted to discover that St. Thomas’s Abbey in Brno is where Mendel conducted his pea plant experiments and that there was a whole museum dedicated to his work at the monastery where he lived and worked.

So of course, I went.

The Value of a Second (and Third) Chance

Gregor Johann Mendel was born Johann Mendel on July 20th, 1822 to peasant farmers on the Moravian-Silesian border of modern-day Czechia. He learned the basic principles of cross-pollination working with fruit trees on the family farm as a boy, a pastime that would become the basis for his experiments. As a young child, he showed great aptitude for learning and his family supported his education despite having very little means. They put everything they had into his education, seeing him as the great academic hope of their family. He also suffered from disabling anxiety and depression that would leave him prostrate in bed for weeks. As a teenager, Gregor found himself without the financial resources to continue his education so his younger sister, Theresia, willingly gave up her wedding dowry so he could pay for his tuition. Even though he was the oldest child, when his father became ill his younger siblings took over the family farm. Later, when he found himself again without financial resources to continue his education, he joined the Augustinian priesthood. He was delighted to be back in school but he was a horrible priest and did a very poor job of consulting and guiding people through the difficult times in their lives. Luckily, one of his mentors, Abbot Cyril František Napp, convinced the clergy to allow Mendel to shift his service to becoming a teacher instead.

And yet this path, too, was fraught for Mendel.

His debilitating anxiety made it impossible for him to pass the oral examination. He failed his teacher exams twice before the church sent him to Vienna to be further educated. In 1853, on the third try, Mendel finally passed his exams. This was a turning point for Mendel, and he began to settle into his life as an educator and researcher. It was at this point that he started teaching physics at the local schools in Brno and soon after began his pea plant experiments in a greenhouse at the monastery in 1856.

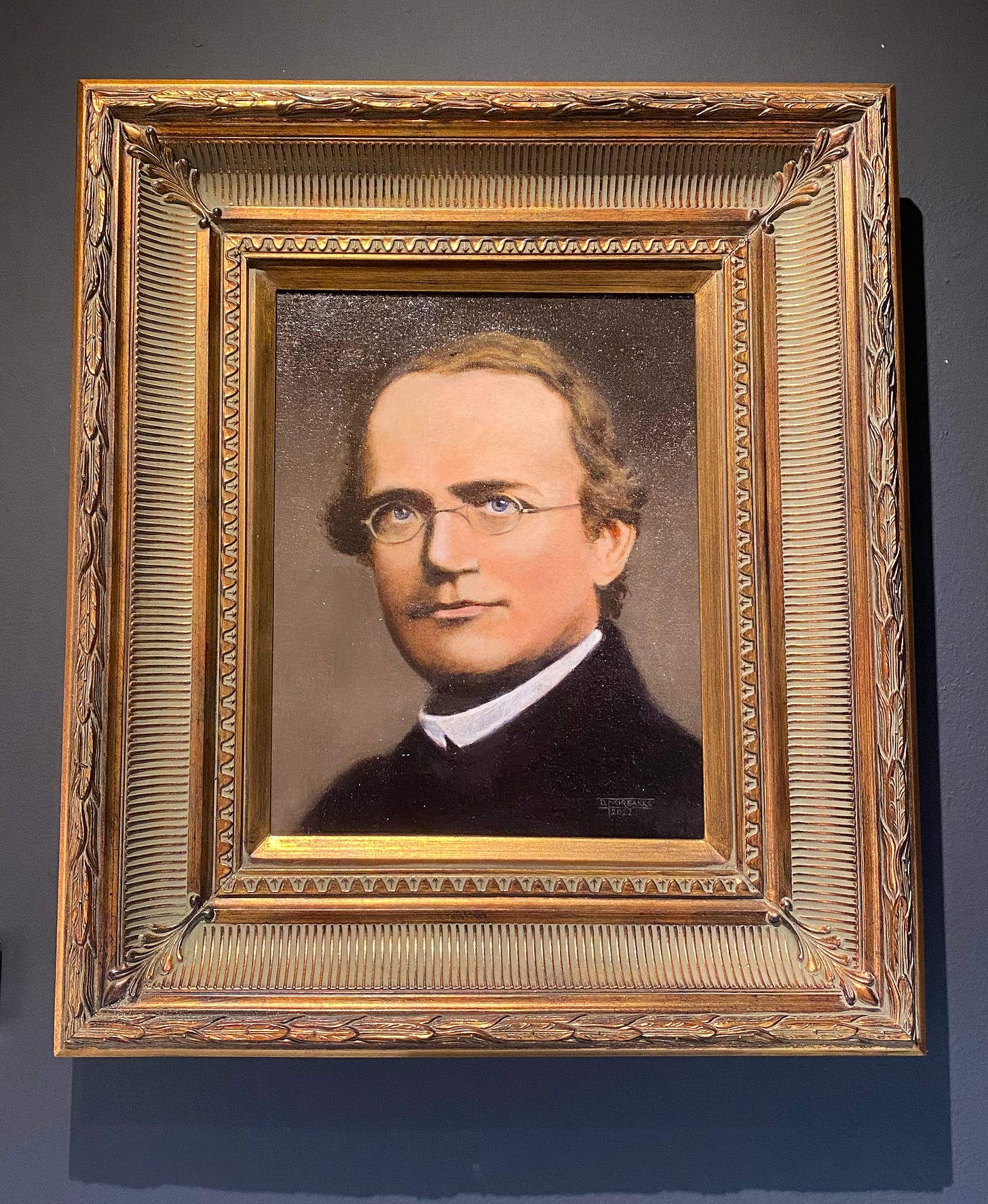

As I stared through the museum glass at an antique set of specimen slides, his gilded bronze microscope, and the wireframe glasses he wore for his abysmal eyesight, I felt deeply connected to Mendel. Part of it is that I love microscopes. The very first thing I bought for myself as a little, bespectacled kid was a microscope set. I used to sit in my basement for hours finding all manner of things to fit on a slide and inspect. I have always liked the discovery part of any process. Another part of it is that I identify with his failures. Life has not been a straightforward roadmap for me, and sometimes it feels like I’m heading nowhere. Stories like Mendel’s remind me that the sum of who we are might be unknown to us in the moment, but ultimately lead us somewhere extraordinary.

At a little interaction station in the museum, I sorted dried peas like the brothers of the Brno monastery did for Mendel for years. The basis of the famous experiment had to do with sorting pea seeds that were different combinations of wrinkly, round, green, and yellow. By cross-pollinating in different combinations, Mendel was able to see how the offspring of the cross-bred plants inherited different traits from the parent plants. Between 1856 and 1863 Mendel cultivated and tested some 28,000 plants at the monastery, and his fellow monks would help him sort according to the seven traits that Mendel was interested in: seed shape, flower color, seed coat tint, pod shape, unripe pod color, flower location, and plant height.

It was through this meticulous sorting (for years) that Mendel was able to deduce that when two true-varients of pea plant were bred with one another, in the second generation, one in four pea plants had purebred recessive traits, two out of four were hybrids, and one out of four were purebred dominant. The discovery of this pattern would form the basis for the Law of Segregation, the Law of Dominance and Conformity, and the Law of Independent Assortment — known now as Mendel’s Laws.

He presented his paper, “Experiments on Plant Hybridization" at conferences in Brno in 1865 and published his findings in 1866, but was largely ignored by the scientific community. It wasn’t until 1900 when three scientists — Hugo DeVries, Carl Correns, and Erich von Tschermak — each independently rediscovered Mendel’s experiments that the value of his research was truly understood and Mendel’s Laws emerged to form the basis of modern genetic inheritance theory in the global scientific community.

What does this mean? Mendel’s work set the foundation for our genetic understanding of trait inheritance, which, combined with chromosomal inheritance theory, led to the chromosomal mapping of the fruit fly by 19-year-old Columbia student Alfred Henry Sturtevant, a student of T.H. Morgan, in 1913. Then in 1953, using the initial research of Swiss chemist Friedrich Miescher and others, James Watson and Francis Crick discovered the double helix structure of DNA. Now we know that genes reside on chromosomes which are made up of strands of double helix DNA, and those genes are passed down through generations of heredity based on Mendel’s laws.

(Perhaps it goes without saying, but all of these scientists failed miserably before breaking through in their research.)

The field of genetics has advanced rapidly since Mendel’s initial discovery and has become commonplace in our lives through advancements in gene therapy and consumer genetic testing services like 23andMe. Much like the advent of the smartphone, the fruits of his discovery have been woven into the fabric of our modern lives. It was Mendel’s initial discovery (and Morgan, Watson, Crick, and many others) that ultimately led to the Human Genome Project. We have his legacy — along with current scientific innovators like badass immunologist Dr. Kizzmekia Corbett — to thank for the genome sequencing involved in the creation of the SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. Looking out of the arching windows of the cavernous abbey onto the courtyard that once held Mendel’s greenhouse, I was reminded that there is something incredibly sacred about being given time, resources, and grace in the pursuit of innovation.

Mendel and his story exhibit traits that I believe are shared by innovators and change-makers in any field: the willingness to push forward through failure, to be seen as an outlier, to overcome mental, emotional, and physical obstacles — and to doggedly pursue the breakthrough. He also had vital support from the church, mentors, professors, and his family. Something that really struck me about his story was how consistently supported he was by everyone around him through his struggles, both mental and financial. As the son of peasants, he didn’t have the money to go to school. As an anxious person, he was prone to bouts of major depression that were debilitating. Throughout these hardships, he was lifted up by the community around him — again and again given the time, space, resources, and grace to learn and grow. These were the conditions under which both he and his pea plants could thrive. We say it all of the time, but it really does take a village to publish that book, to get FDA approval for that product, or to launch that app.

Without significant and consistent community support — and his ability to overcome failure — Gregor Mendel might have never made it into that greenhouse.

The Invisible Infrastructure of Innovation

While working on a documentary project in college, I had a mentor tell me, “I hope you know, filmmaking isn’t glamorous.”

She was right. The process of making a movie is hard work, the editing is often done in a dark room without windows with horrible fluorescent lighting, and the thing will look like nothing until it comes together, and no one will see the struggle, only the result. I think this is true for the creation of anything, whether it’s putting on a play, writing a book, building a bridge, conducting experiments, or designing an app. The world will only see the result of your work, not the long, winding, weird, beautiful process that it took to get there. The world may also not know the true depth of support it took for an artist, engineer, scientist, or founder to arrive with enough stamina, self-esteem, and drive to cross the finish line.

One of the most popular shows of the 21st century, Game of Thrones, initially shot a ten-million-dollar pilot that was all wrong. Ten million dollars. The first-time showrunners, David Benioff and Dan Weiss, just didn’t pull it off. It was an extremely expensive flop. They went back to HBO, admitted failure, and begged for a second shot. The world was reimagined and some actors recast before the pilot was shot again for millions of dollars more. It was that second chance pilot, notably with new cast member Emilia Clarke as the iconic Daenerys Targaryen, that would capture the attention of the world and become the initial cultural imprint for a TV show that would go on to gross $3 billion in revenue.

Before Microsoft, Bill Gates and Paul Allen founded a company that none of us have ever heard of: Traf-O-Data. They were in high school and the premise of the company was to create a machine that would make analyzing traffic data easier for municipalities. Teenage kids without high-powered computers of their own, the pair used a computer lab at the University of Washington to build the company. But the duo was undeniably green, hadn’t done market research, and ultimately municipalities didn’t bite on the product. It was a half-baked venture and a business failure. In the process of building Traf-O-Data, however, Gates and Allen learned crucial knowledge about microprocessors that would become the foundation of the technology they would build with Microsoft.

Can you imagine what the world might have missed out on if HBO refused to support reshooting the pilot? Or if investors had refused to back Microsoft because Gates and Allen’s first business hadn’t been a commercial success? Or if Mendel’s mentors had given up on him after his second failed attempt to pass his exams? The abbey that housed Gregor Mendel’s monumental discovery is plain and ordinary; four walls, a floor, double-pained glass windows, and ample light. What you see is the basic structure that housed his innovation. What you don’t see is the invisible infrastructure that supported his growth: the practical building blocks of time, housing, food, clothing, lab equipment, education — and the ethereal building blocks of forgiveness, compassion, and grace. The unwavering support from his family. The understanding of his illness by everyone in his life. The dowry his sister gave up to fund his schooling1. The continued financial support of the church. What you don’t see are the failures and the setbacks; the months he spent in bed riddled with anxiety; his failed attempts to pass university exams; the years of unsuccessful experiments before his breakthrough; and the lack of understanding of his work by his peers.

Americans love to romanticize an underdog story — scrappy heroes beating the odds all by themselves. And yes, picking yourself back up after failure is a big part of success. There is no innovation without experimentation and no experimentation without failure. But there is also no innovation without support. There isn’t a single successful person today who wasn’t supported through their struggles in some way; and not a single breakthrough discovery that wasn’t financially funded through the failures of experimentation. And yet, the horrible phrase “pick yourself up by your bootstraps” is still seared into the American consciousness despite the obvious absurdity of the statement. It comes from a political cartoon in the 1800s and was literally meant as a joke; no one actually picks themselves up by their bootstraps. It’s physically impossible. Still, the American mythos so often glorifies the triumph of the individual and ignores the monumental impact of the community of people who are there to dust you off and pick you up after you fall. You don’t have to go far to find a “self-made” success story.

But the truth is success is actually “community-made.” Mendel was given his sister’s wedding dowry; a second (and third) shot at passing his teaching exams; and an order of brothers willing to sort pea plants for years without knowing if it would pay off. Benioff and Weiss were given another $10 million dollars to reshoot their disaster of a pilot. MITS founder Ed Roberts gave Bill Gates and Paul Allen a pitch meeting to demonstrate the Altair BASIC interpreter they created based on their Traf-O-Data emulator. And despite what she might have to say about it, even Ayn Rand’s protagonist Howard Roark in The Fountainhead had a leg up. For some reason, despite his personality, people kept hiring him.

Innovation requires community investment, even if the first (or second or third) round didn’t work out. Taking the lessons from our failed attempts for the next time around is how we learn and grow. We don’t often think about it, but 90% of clinical trials conducted by drug manufacturers are unsuccessful. It’s only 10% that we see out on the market. Failure is a huge part of the process of finding new treatments for life-threatening conditions like HIV, cancer, heart disease, and diabetes — and so is continued financial investment to find solutions.

It is curious to me that Mendel discovered the foundations of genetic inheritance while struggling with mental health issues that were likely a result of genetic inheritance within his own family2. I am very happy that the field of epigenetics, the science of change, has come along to give nuance to this notion that we are defined by our genes. The more we discover about our genes, the more it is clear that we are not beholden to that initial inheritance. Mendel himself proves that our initial inheritance is only the beginning of the story. With the right support and resources, innovation can thrive in unlikely places, like the greenhouse of an old monastery in Moravia or a garage in Albuquerque, New Mexico. In addition to the science stuff, that is our inheritance from stories like Mendel’s. Perseverance through fear of failure. The positive impact of community and family support. The grace of being given a second chance.

No person is an island and no person is perfect. We all struggle with the cards we were dealt in this life. We all make mistakes. And we all deserve love, support, and guidance as we find our way in this world — especially the people in our lives who are working within identities that often aren’t automatically offered a second chance like Mendel was. It is not a coincidence that this story I’ve just told you about success through failure, and almost all of my anecdotes, have been stories about white men. So give and receive support freely. Pick people up when they fall down — and accept a helping hand when it’s you on the floor. Expand your worldview about who deserves your time, money, compassion, forgiveness, and grace. Start with yourself. This is where initial inheritance begins, after all.

Who knows? There might be a great work of art or a monumental discovery on the other side of that vital support.

Resources

Historical Figures - Gregor Mendel - such a good podcast about Mendel’s life. I highly recommend a listen!

Gregor Mendel and the Principles of Inheritance

How we got from Gregor Mendel’s pea plants to modern genetics

Mendel notably put Theresia’s sons through medical school, her sacrifice not forgotten.

According to the Historical Figures pod, Mendel’s father likely also suffered from anxiety.